ARTIST INTERVIEWS SFAC Equity Interviews

Lenore Chinn

Lenore Chinn was born in San Francisco and has spent her entire artistic career as a painter and photographer living in the City. h3>She is a founding member of the Queer Cultural Center (QCC) an original member of Lesbians in the Visual Arts, and an active member of the Asian American Women Artists Association. Chinn has also served on the SF Human Rights Commission. She continues to exhibit her work and advocate for the legacies of Bernice Bing and other Asian American queer visual artists in the Bay Area.

Lenore Chinn

Beth Stephens & Annie Sprinkle (B&A): Lenore, please introduce yourself and describe your work and career?

Lenore Chinn (LC): I was drawing ever since I was a little kid and I had a natural gift. Later, when I enrolled at City College of San Francisco, there were two art departments: one was oriented towards commercial work, called Advertising, Art and Design; the other was called the Fine Arts department. For whatever reason I ended up in the commercial one where I actually I picked up a lot of skills: I got introduced to photography, I learned to develop black and white film, to shoot with a 4x5 graphic view camera, and to do printmaking. Ultimately, I got my AA (Associate in Arts) in Advertising, Art and Design. Later I got a BA (Bachelor of Arts) at San Francisco State in sociology.

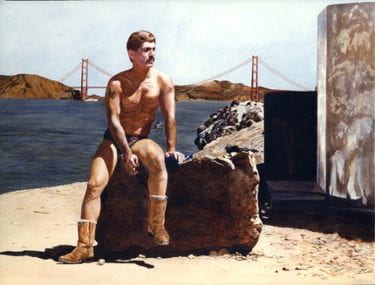

Lands End Tris Evelio Talavera

Lands End Tris Evelio Talavera[/caption]In the early days I would do commissioned portraits. But that wasn't my favorite thing. I don't really like to do the kind of portraits most clients had in mind. I'd rather not be restricted by someone who just wants to create something to put over their sofa.

Lands End Tris Evelio Talavera

In the 1970s I was at San Francisco State, the war in Vietnam was still going on and the college’s Ethnic Studies programs had barely come into being. I took a lot of photographs of the cops on campus in full riot gear, on horses, on motorcycles, (most likely the infamous TAC Squad that had come out during the earlier student strikes in the year or two before my arrival).

…. So, when I've gone back to give talks in their Ethnic Studies classes, I would show the students these photos and their jaws would just drop. These photos were taken at the same time when the students were shot at Kent State; May 1970. I was right in the thick of what was going on. I reminded the students to pay attention, because we're still going through similar wars. That has not changed.

(Note: I went back to SFSU to see the encampments of students urging the university to divest from any U.S. funds which may going toward the genocide of people in Palestine and specifically, Gaza).

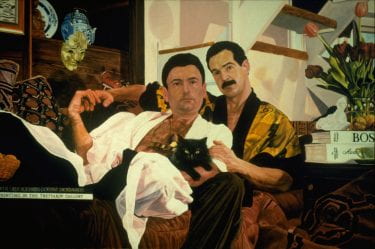

So, I started painting the lives of the people in my immediate circle who were largely lesbian, gay and people of color as my subjects. My style in painting was super realistic. Drawing people was just a natural thing. Mainly I painted my friends. That's often the case, that artists paint the people in their immediate circle.

For many years photography was my secondary expressive medium, chronicling events as I do now, but mainly creating concepts for my paintings.

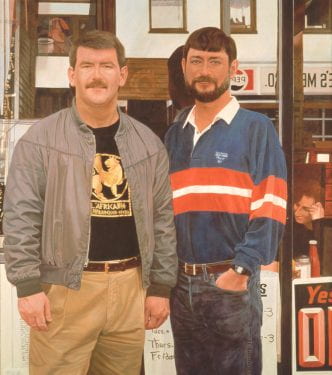

Domestic Partners, 1989

Jeff Jones (JJ): Lenore, I feel like you have an essential perspective on this chapter in history because when I arrived in San Francisco in 1979, you were one of the first artists I met here. So I'd like to hear your perceptions about what individual artists were around before I got here. Because, except for maybe Adele Prandini’s It’s Just A Stage, I don't think there were any other Queer arts organizations before 1978, when Theater Rhinoceros and the Gay Men Chorus were founded.

LC: My recollections going back 40 years may be kind of fuzzy. There's a lot of overlap in who I met when and where. When I first started showing my work, the gallery system, as it came to be known, had not yet taken root. Today it is much more focused on commodity, commercialization, and profit making. One of the first places I exhibited was the Lucien Labaudt Gallery, run by his widow Marcelle Labaudt. According to my late uncle, the photographer Benjamen Chinn, my getting into that gallery was a great achievement. But I was submitting my work to all kinds of different venues, mostly alternative spaces and to competitions juried by notables in the Bay Area or around the country.

One of my first exhibitions was in a group show located at San Francisco Arts Commission’s Capricorn Asunder Gallery. This 4-person group show was curated by the late Bob Hanamura, whose salary was paid by Jimmy Carter’s Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) program. That was in 1980. I was also involved in the San Francisco Arts Festival (NOTE: Art in the Park was not affiliated with the SF Arts Commission and that event was held in Golden Gate Park, not Civic Center. It was produced by Frank Pietronigro and sponsored by the Castro Street Fair Non-Profit Corporation). held outdoors in the Civic Center. I got my start by responding to calls for artists and by submitting slides of my work everywhere I could find opportunities.

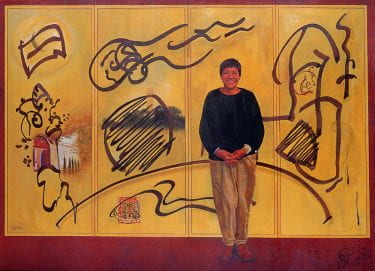

Bing

JJ: When you started your career here in San Francisco, what other gay or lesbian artists did you know? How about the painter Bernice Bing? When did you meet her?

B&A: Her paintings are incredible!

LC: Not until about the last 8 to 10 years of her life. I met her through 2 sources. One was through L.A. “Happy” Hyder because I was involved with the group Lesbian Visual Artists (LVA) just before I got involved with QCC. Around the late 1980s and early 1990s I was part of a group who organized an exhibit in the rotunda of City Hall because somebody in our group, Dori Friend, worked there and had access. I met a lot of people through the course of all my art explorations That is how I got to know Richard Bolingbroke who started the Gay and Lesbian Artist Alliance in 1989. Somewhere in that time I got to know Valérie Jacobs who recently died on March 7, 2024.

JJ: When did you meet artist Rudy Lemke?

LC: Not until you guys got us together after the San Francisco Arts Task Force formed in 1990 or 1991. In terms of the individuals who ultimately formed the Queer Cultural Center’s initial Board of Directors, I knew Adrienne Fuzee who was on the board of LVA and I might have known Osa Hidalgo-de la Riva. Adrienne ran Spectrum Gallery near the foot of the Bay Bridge. She would curate projects in what today we would call pop-up galleries.

JJ: She was one of the very few lesbian curators I met. She was an impressive person; unfortunately, she died soon after I met her. The first time I remember seeing your work it was at that South of Market lesbian bar, dance club, and hostel on Clementina Street called Clementina’s Bay Brick Inn but it went by several names (see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clementina%27s_Baybrick) run by Lauren Hewitt. Earlier you mentioned that your Uncle Benjamen Chinn was a really great photographer. Was he your main role model when you were growing up?

LC: Yes. I had two great role models. The other one was my dad, William G. Chinn because he was really ahead of his time in a lot of ways. He was a mathematician but he exposed our family to all kinds of art. We lived out in the Richmond district in the 1950s at a time when there really were very few families of color out there. It was a pretty segregated neighborhood. But my father took us to the de Young Museum and the Legion of Honor (formerly known as the California Palace of the Legion of Honor), on a regular basis. He also took us to see plays and musicals downtown.

Melorra Green

My uncle and my dad were pretty close. I grew up hearing stories about my uncle's travels and his photography. He brought a camera, with flash bulbs, to every family gathering. He didn't realize the impact he had on the artists of my generation. He went to the California School of Fine Arts, which later came to be known as the San Francisco Arts Institute. Hearing these stories had a big impact on me because he made me aware of what was possible.

JJ: Where did you meet Rick Pacurar and Michael Housh? The Milk Club? The three of us worked together in the 1980 US Census. Rick Pacurar, in addition to being Supervisor Harry Britt's roommate, was an assistant to Mayor Art Agnos and congressman John Burton before he died of AIDS. Michael Housh also worked for John Burton before he became the City of San Francisco’s archivist. Your portrait of these two gay men was the first one of your works I looked at critically.

B&A: What was the Milk Club and where was it?

JJ: The Harvey Milk LGBTQ Democratic Club was originally founded by Harvey as the SF Gay Democratic Club in 1976 to provide a Progressive alternative to the more conservative Alice B Toklas Club.

LC: I joined this Club around 1980 and co-led the Club’s Women’s Caucus along with Tish Pearlman. We advocated expanding the Club to include more Lesbians. The name changed to reflect that inclusion, from the Harvey Milk Gay Democratic Club to the Harvey Milk Lesbian and Gay Democratic Club. I don't know the people in it currently; it's been a few generations.

Chinn and Tricia

JJ: I started going to both Harvey and Alice in 1979. I noticed there were very few lesbians at the Milk Club and not many more at Alice. Both Clubs were very male. Why did you join Harvey as opposed to Alice?

LC: I can’t give a definitive answer, but I kept running into a lot of their members. I probably went to some meetings in the early eighties to hear people like Dr Marcus Conant who was talking about what was going on in the community before AIDS had a name.

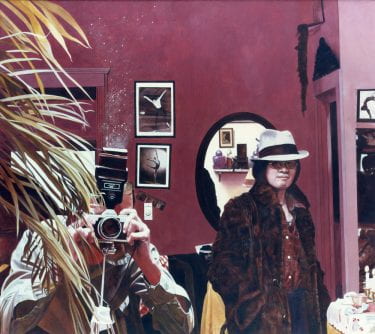

JJ: So I also remember you did a portrait of painter Kim Anno (who recently became a Guggenheim Fellow) and her wife Ellen Meyers. How did you know Kim?

LC: Kim and I met in a project at the South of Market Cultural Center in the 1980s when she curated one of my paintings of a black cat. She also knew Adrienne Fuzee.

JJ: I remember seeing that picture several times, perhaps it was hanging in Moira Roth’s house.

LC: Yeah, they were pretty close. Moira, who was the Trefethen Professor of Art at Mills College, helped Kim when she was trying pursue a teaching job at the California College of the Arts. Note: The image Jeff probably saw was the original photo on which my portrait of Kim Anno and Ellen Meyers, titled “Before the Wedding,” was based.

JJ: Beth and Annie, did you know Moira Roth?

Beth: We both knew her and we loved her. I knew Happy Hyder and Adrienne Fuzee too. At one point, I think Adrienne and Happy lived together in Oakland.

Note: Adrienne and Happy (L.A. Hyder) shared an apartment on 11th Street in Oakland.

LC: She used to host great salons.

JJ: Adrienne was one of the founders of the Queer Cultural Center(QCC).

B: I had a crush on her. She was very striking.

JJ: So Lenore, who recruited you to be on QCC’s board?

LC: You did.

JJ: Me. Okay. I couldn't remember if it was me or Pam Peniston or Greg Day.

LC: You threw out the idea of a gay museum when we were sloshing drinks with Pam and probably Rudy.

JJ: I didn't know either Pam or Rudy until we found ourselves on that Task Force the City set up to deal with the aftermath of Festival 2000.

LC: Yeah, I heard all kinds of stuff about it.

Affirmations

JJ: That's where I first met Flo Oy Wong. Because after I put out my report entitled “Institutionalized Discrimination at Grants for the Arts” in 1987, either Moira Roth or probably Flo Oy Wong called me up and said I want to meet you. I volunteered to cook dinner for six. In addition to Flo and me there were 4 other people: Carlos Villa, Flo’s brother Bill Wong, Moira Roth and Betty Kano, a Japanese American painter who had been at SF State during the ethnic studies struggle in the late 1960s.

So, I had dinner with almost five complete strangers. Moira suggested that we go around the table and introduce ourselves; this process took over an hour. After my guests left, I realized that my report or race and the arts, was significant. Although the Chronicle’s response was to run an editorial that said that art and race had nothing to do with each other, I was universally greeted with derision by the “professionals” in the arts world. On the other hand Bill Wong, who was the only Asian American nationally syndicated columnist in the United States, later published an article, which discussed San Francisco’s Arts Apartheid Policy.

AB: Lenore, please tell us about Flo Oy Wong. Who was she and what did she do?

LC: Flo Oy Wong is a Sunnyvale based artist and now a poet. There's a film that just came out called “Drawn from life: The Creative Legacy of Flo Oy Wong.” It was recently completed and shown at the Silicon Valley Asian Pacific Film Fest. It was nice to see on the big screen. Plus there’s gonna be a mural going up with her work at the restaurant where she and her family worked in Oakland.

JJ: I met Flo before my dinner when she contacted me and asked me to help her raise funds for an exhibition of Chinese American painters that would be included as part of Festival 2000. I was very interested in having an inside perspective on Festival 2000, which had been set up by Grants For the Arts in response to my report. Flo convinced Festival 2000’s Executive Director to commit $30,000 or $40,000 to the exhibition. But then the Festival went bankrupt after 4 days, and the directors shut it down, leaving everybody holding the bag, including Flo.

LC: Flo said she was in tears because she thought, oh my God, we've lost all this money and what are we gonna do? She said René Yañez calmed her down. He was a trip and a half. The community is so small that if you're here long enough you meet everybody.

JJ: That's true. If you're as old as we are, you eventually meet almost everybody. Flo suddenly dragged me into raising money for that event and that’s where I met Bernice Bing for the only time in my life.

LC: Bernice died the same year as my mom, 1998.

JJ: So that was in 1990, Festival 2000. In 1999, “They Hold Up Half the Sky" - "Bernice Bing: A Memorial Tribute and Retrospective,” was co-curated by me along with Flo Oy Wong, Moira Roth and Kim Anno at the South of Market Cultural Center. The Executive Director of the South of Market Cultural Center Jack Davis had known Bernice from their early days there. The other half of the project was the 5th anniversary celebratory exhibit of the Asian American Women Artists Association.

La Happy Hyder Cafe International

LC: We got together down at Jack Davis’ office. He had known Bernice from the early days when she had been the first Executive Director of the at the South of Market Cultural Center. He wanted to have some kind of a tribute for her because of her involvement with the Center. That's when we pulled in the Asian American Women Artists Association (AAWAA). It was on the verge of its 5th anniversary that year, then QCC was kind of behind the scenes because Rudy was putting the website together for all of those things.

JJ: I was writing the grant.

LC: The Asian American Women Artists Association was the other way I knew Bernice.

JJ: Because of that, I spent a lot of time with Flo Oy Wong and later we hung out with her brother Bill too. He wrote a nationally syndicated column that talked about Grants for the Arts as arts apartheid policies in San Francisco. That flipped people out, as you can imagine, Kary Schulman, the Director of Grants For The Arts was livid.

LC: I saw Bill Wong the other day at a film festival. He's trying to navigate without his wife Joyce, who passed last year. He has a new book coming out that focuses on their father. Well, maybe you know about this. Brenda Wong Aoki and Mark Izu just had a production at the Presidio Theatre entitled “Soul of the City” that was spectacular.

JJ: Yeah, Marie Acosta saw that too and she said the same thing.

The other thing I wanted to talk to you about was the lesbian blood drive that you did during the AIDS crisis. How did you decide to do that?

LC: Well, some of us in the Milk Club were trying to figure out what kind of projects we could do to support people with AIDS. We heard about a blood drive that was done in Santa Cruz. The women's caucus decided that we would create something like that. Dawn Moore, one of the Milk Club members, had a connection to Most Holy Redeemer Church in the Castro. We worked it out so that we were able to have the mobile blood draw unit of the Irwin Memorial Blood Bank (Note: the name has changed to Blood Centers of the Pacific) come out. It all ran pretty well until we ran into Dr. Lorraine Day, who was a Seventh Day Adventist. I don't know if you remember that controversy, Jeff, but she tried to shut us down.

Before the Wedding

There was another smaller blood drive called Arm in Arm run by a nurse friend of mine named Penni Kimmel. She was basically told to cease and desist because Dr. Day used her influence and was telling outright lies. Dr. Day had no knowledge of what was going on, but she presented it to the health department that we were collecting tainted blood.

Because of my connection as a healthcare worker with California Pacific Medical Center at the Davies campus, I knew a lot of doctors and nurses. They helped me create a petition to counteract the stories that she was telling. Anybody who knew anything about what was going on with the blood drive knew we weren't collecting from gay men. At that time the guidelines were pretty narrow. Gay men could not donate to those blood drives. Not that lesbians can't get AIDS, but in those days it was crazy because people literally thought you could get AIDS standing next to somebody in an elevator. Davies got freaked out because some of the patients who were not sick would see all these guys coming in who really looked like death. So they got the hospital to acquiesce to put in a separate elevator so that patients who had HIV/AIDS would be going through a different elevator to get to various parts of the hospital.

At Davies we had a large population of patients with HIV and AIDS coming through because of where we were located; Castro and Duboce. Eventually we got Dr. Day to back off and the blood drive continued for about 9 years.

JJ: Wow! It went on that long.

LC: It wasn't like if you donated blood, it would go directly to a person who had HIV/AIDS. Because that's impossible logistically. But it allowed for our account to accumulate credits. A lot of people with AIDS were getting blood transfusions because of AZT, which was one of the primary drug therapies. AZT had a side effect of anemia. I think our patients saved about $75 a pint. So it was a financial benefit for those who applied for credit.

B&A: Lenore, what job did you have in health care?

LC: I was a clinical laboratory assistant and an assistant to the pathologist. Part of it was clerical and part of it was assisting pathologists, doing things that did not require a license.

B&A: Did you have that job because you were an artist on the side or were you an artist first?

LC: I was looking for a job to essentially subsidize my art practice and friend of mine from college was working there and heard that there was a job opening. I was looking for part time work to subsidize my art practice. In those days it was pretty easy to get work with referrals and whatnot. Now there's like all this crazy bureaucracy. She referred me and I talked to the head pathologist. At that time it was called Franklin Hospital. Before that, long before that, it was called German Hospital, but during and after World War II, that wasn't too popular so they changed its name to Ralph K. Davies Hospital.

JJ: He was an oil billionaire whose wife Louise is the namesake of Davies Symphony Hall.

LC: So I worked there for about 35 years. I started working just on weekends. Then I worked in the evenings full time. Eventually I cut my hours to part time, but I still could keep my full medical benefits… dental, and vision. You can't get that kind of job anymore.

John Paul Marcelo

JJ: On my way out of town in 1984, I went to Davies to see Allen Estes. He was one of my closest friends. I was gone for 3 weeks. When I got back, he had passed away. That was just what happened back then. He was the founder of Theater Rhinoceros and the first producer of The AIDS Show. But he died before it opened. I'd like to talk for a minute about your relationship to the San Francisco Cultural Equity Grants program. How many grants did you receive from them?

LC: The only grant I have ever received was in 2011. You didn’t write it. Rudy and Pam Wu assisted me with it. Over the years I had seen what you had written for other artists and groups and that was a nice template.

By then I knew Laurie Lazer and Darryl K. Smith from the Luggage Store Gallery where I did a show called Family Album with Steve Compton, a friend of mine. That was one of the first projects I did that included Flo Oy Wong: Steve and I had heard about her work and saw her pencil drawings of Oakland’s Chinatown at the Oakland Museum. Then I got familiar with the Luggage Store and I co-curated a show there. Then I did other projects because I was on a jury with Carlos Villa there.

JJ: Yes, he was the chair of the board.

LC: I had a long relationship with Carlos and he was really close to Moira Roth.

JJ: He and I were also very close. He was my mentor and the person who taught me how to talk about things from the outside, from the ‘other’ perspective. He said there's actually two ways you can look at this. One is from the inside, one is from the outside. You're from the outside because you're queer and you should incorporate that into how you think and talk. I was like, wow, that’s really smart. That was around 1989.

We stayed in touch until he died in 2013. I still miss him very much because he was the one who really pushed me through that door, and many other people too. He said, “I've been in San Francisco a long time and I was at the Art Institute way back when there were people of color and queer painters in the fifties and early sixties that nobody really could remember.” Then he did that show about the “early expressionists,” as he put it; Rehistoricising the Time around Abstract Expressionism in the San Francisco Bay Area. That was at the Luggage Store and was really an amazing exhibition.

LC: Emael Haasalum helped him create a website and it's still live. It includes my information about Bernice and there are a bunch of people in there. https://rehistoricizing.org/ Bernice was in that show because he asked if we could get a hold of some of her work. I knew Alexa Young, the Executor of Bernice’s estate. So we were able to include a couple of her pieces in that show.

B&A: When was that show?

LC: It was June 4 – July 31, 2010

B&A: Does the Luggage Store have things like their catalogs and ephemera organized? Is everything still there?

JJ: No. The Luggage Store is the place where an incredible number of artists of color had their first shows and who became really, really, really famous.

Were there any other LGBT painters? in the Family Album exhibition that you co-curated with Steve Compton?

The Family ,1991

LC: The artists in Family Album had work in a variety of media and included, among others, L.A. “Happy” Hyder, Osa Hidalgo-de la Riva, Lola de la Riva, Orlonda Uffre, Greg Day, Maude Church, Steven Compton, Flo Oye Wong and myself. Years later (2013) I curated a separate exhibit there called “Flo Oy Wong: The Whole Pie.”

JJ: There was a show named “Face” that was all portraits…

LC: That was the first show that Rudy Lemke and I co-curated and organized. That was huge.

JJ: Yeah, it was the opening night of the first National Queer Arts Festival

LC: We were still dealing with slides in those days. That's how long ago it was. Everything was sent by snail mail. One day Rudy said he got a death threat because he didn’t include someone in the show. I don't know if somebody actually went to his house and rang his doorbell. We laugh about it now.

JJ: There is a catalog that I have somewhere in my archives.

LC I designed the program. We printed boxes and boxes of those catalogs. I'm sure Pam has some in her basement too.

JJ: I'm sure she does.

When I think back now on people that were on the original board of QCC it included people like Blackberri and Adrienne. You, me, Pam and Greg, Osa Hidalgo-de la Riva, and Freddie Niem.

LC: He's the one who took that picture of all of us.

B&A: Has your archive been placed somewhere yet?

LC: No, but I have received overtures from various places that want me to keep them in mind. There's a woman coming out from the Smithsonian soon who wants to talk to me and she wants to see my work. She also wants to see my uncle's work, even though my cousins and I don't have too much left because his work has already been distributed to various archives. We had so much stuff at one point that we just wanted to make sure that our uncle's work was safe. When he was still alive, I asked him where he would want his stuff to go. He said the Center for Creative Photography, which is a national photographic archive in Tucson, Arizona. That's where a lot of his friends’ work went, like Edward Weston, Minor White and others my uncle knew have their photographs archived there. Minor White, was gay. So, we got a lot of stuff placed there and then later we placed some stuff with SFMOMA.

LC: Oh, the Cantor took a batch of his vintage photography. One of his photographs is on view right now. So we went down to take a look.

B&A: Cool. What's your greatest achievement, in life and or art?

LC: How do you define achievement? There have been a lot of little highlights. Not so much as an artist per se, but in the arts. I think it was elevating Bernice Bing’s legacy. She had really lapsed into complete obscurity and died too young.

It took 25 years to get her into any major art museum until Abby Chen, who became the Head of Contemporary Art and Senior Associate Curator at the Asian Art Museum, reached out to me.

I was just talking to my cousins and realized that because of my work helping Bing, I was later able to do similar legacy advocacy thing for my uncle.

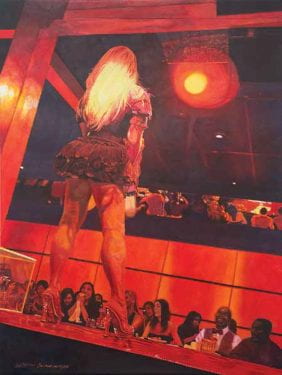

I don't know if you guys would know or remember Freddie Kuh. He was the guy who owned the Old Spaghetti Factory back in the day. That's where she had her studio. At one time, she worked there as a cocktail waitress. Well, I think Freddie had like maybe 3 of her works. When he died, I think he willed them to the Oakland Museum. But they declined them. Because of course nobody paid attention to her at that time. You know what I mean? Like who the hell is she? A person of color, a lesbian, those were all obstacles that were present. They said we cannot honor this bequest and we will not take care of these works in perpetuity.

Déjà Vu, 1986

So Kim Anno said, “I'm just gonna go down there with my truck and pick them up.” So that was how one ended up at the de Young Museum. They had been interested earlier, but when they talked to Bernice earlier, she had not been in a position to be giving work away. She used a lot of her work to pay dental bills and things like that. So Flo and I went and asked Timothy Anglin Burgard (the Distinguished Senior Curator and Curator-in-Charge of American Art for the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco) if he would still be interested in an acquisition. This was also a tip that Elizabeth Cornu, our friend who used to be an arts conservator, gave us. She said, “you need to start placing them in different institutions if you can, so they can get on the radar through their registries and people will begin to notice and take them seriously.”

That's how we started and managed to get one small oil painting in there. Over the years, step by step, we got her into shows. The biggest exhibit, up until the Bing estate, which got her into the collection of the Asian Art Museum was the Sonoma Valley Museum of Art. That one caught people's attention. When filmmaker Madeleine Lim came along and hooked up with the Asian American Women Artists Association, they were looking for a project. Bernice Bing was one of their early members. It was like, how can we put all these pieces together to honor and elevate her. It's a great legacy. When the Bing Estate got an exhibit at the Sonoma Valley Museum of Art there was a really great turnout of the Asian American arts community. There was a great write-up by Charles Desmarais who was a San Francisco Chronicle writer and was also President of the San Francisco Art Institute at one time.

Then Abby Chen, the Head of Contemporary Art and Senior Associate Curator of the Asian Art Museum contacted me and said she thought that the Asian might be interested. “How do we get a hold of whoever is in charge?” I said, “You should be talking to Frieda Weinstein.” That was before Alexa Young died. Or maybe she was gone because Alexa just died earlier this year. Alexa was the executor and knew Bing from back in the day. So, I contacted Frieda and the two of them worked it out. That's why they have arguably the largest collection of Bing works. There's a lot of Bing ephemera at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford too.

B&A: That's a noble and great achievement and must feel so good.

Lenore, we want ask about San Francisco. We are interested in helping to archive the history of San Francisco’s diversification of culture, and creating more equity and inclusion and all. Do you feel like San Francisco was the epicenter, of that cultural movement? Having grown up here, and having been an artist on the inside, what's your perspective?

LC: I wasn't involved at the beginning. But I've talked to several people about this. Jeff, do you know DeWitt Cheng? He's a local photographer, curator, and writer. He gave me a really good review on the group show that I have photographs in at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, Bay Area Now 9. One of the things we were talking about was an article that came out recently in the New York Times, about how two major galleries pulled out of San Francisco. The Times got a lot of push back from people here because we said, no, there is still an arts community here. But it's very different from New York. A lot of art and creativity is incubated here. The Bay Area is less concerned with profit than what we see in the New York scene. It's a very different thing. We have a lot of alternative spaces and things like that. So art’s purpose here is very different.

JJ: The things that are considered theatrical achievements here usually take place in a 100-seat house as opposed to Broadway, you know? That's always been the history of theater in San Francisco. It's small. A lot takes place in restricted spaces. I think that's true for the visual arts too. Look at the nonprofit galleries around here. Darryl and Laurie, started the Luggage Store with absolutely no money, managed to put together the place where artists who have made millions of dollars have come out of, like Barry McGee and Mark Bradford. There are a bunch of other ones too. That's not what you would consider a major arts institution.

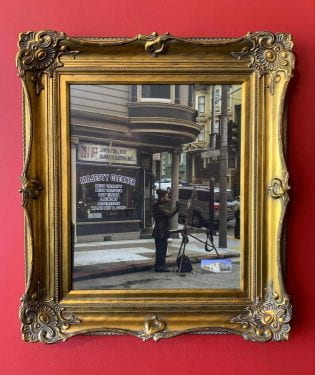

Ceci n’est pas une Pipe, 2010

LC: Who's defining these things? The power brokers in a lot of major museums are a whole different thing. If you're relying on them to be anointed, you're kind of in the wrong game. The other area where I've often been shown is cultural centers and educational institutions. Like I was in Art After Stonewall in New York and that was a traveling show. The first half of the show was at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. The second half was at the Grey Art Gallery, at NYU. I visited both institutions. I think a lot of those areas are where you're gonna see more experimentation and things that are not made to necessarily sell. Although a lot of the people in those places have gone on to bigger and better things, at least in terms of recognition for their work.

B&A: We're curious about Jeff's role in cultural equity and inclusion. Did Jeff write grants for you?

LC: He wrote the grant that got the tribute show for Bernice Bing.

JJ: Yeah, and for Flo Oy Wong’s Festival 2000 show.

B&A: You were out as a lesbian. Did that create challenges for you in the national art world?

LC: I realized very early on that the way the gallery route was structured, was not gonna be a route for me to get my work out. It just wasn't. I had some support initially. I had encouragement from a person who's no longer around, my allergy doctor, William Sawyer. He had a gallery in the Laurel Heights area, called the William Sawyer Gallery. He came to one of my early shows. But there wasn't the kind of connectedness that we see now, when it's more obvious. There was always gay content, but not everybody recognized it. The interesting thing I have found is that the people who really appreciated my work when they saw it were generally lesbian or gay. They could read the iconography with no problem.

Years ago, I was approached by a guy to show my work at the Rasmussen Gallery at Pacific Union College, a private Seventh-day Adventist liberal arts college. So I thought oh why not? I thought he was gay. But he was so freaked out that if we showed these paintings which were largely gay subjects, a bunch of drag queens were going to show up to my opening. I think it was because he was so closeted that he didn't want to trigger anything which might reveal himself. That was probably around the 1990s which is now a long time ago.

Jeff, do you remember Frank Pietronigro? He did Art in the Park. I was in that one.

JJ: Yeah, I remember he tried to revive the Arts Festival the SF Arts Commission held in Civic Center once a year. Are you represented in the Arts Commission collection? Note: The San Francisco Arts Commission used to organize the San Francisco Arts Festival, located in Civic Center for many years. Much later it was held at least once at Moscone Center. I exhibited in both locations. Art in the Park was held in Golden Gate Park by the Bandshell. I exhibited there also and received a blue ribbon from juror Karen Tsujimoto.

LC: No, but I got a purchase award from them in 1977. That is another one of my weird experiences with the Arts Commission. Parts of them have been pretty dysfunctional, I have to say.

JJ: Yes, until they got money.

Miss Montana Two Spirit, 2019

LC: I was one of a handful of artists who won a purchase award for works that were destined for the newly constructed North Terminal at San Francisco Airport. The building didn't get done on time or whatever. So the painting essentially disappeared. Everybody wondered where my painting ended up. One day I got a call from one of my father's brothers who was working at City Hall as a handyman. My uncle called my parents and said, you better get Lenore to come down to City Hall, because I just got a work order to put this painting up in a back office and I’m pretty sure it’s hers. So, I went down there with my folks and sure enough it was nowhere in the public view as was intended with this purchase award. It took me a while to get it excavated from that location. It became a foray into politics and bureaucracy. I contacted the Arts Commission and they kind of blew it off. They basically said well it's ours now so it's none of your business. You got paid, you should be happy. Then I read an article in the San Francisco Examiner, an exposé about how some of the works that were under the purview of the Arts Commission disappeared, some were damaged, some were destroyed. I mean, famous artists, right? So I contacted the writer and he told me dreadful stories. He said, “oh, I wish I had known about your painting, but at least you know where it is.” Finally I got a hold of Louise Renne who was on the Finance Committee of the Board of Supervisors, I believe, at that time. She heard about it and was like that's not how we're supposed to be spending our money. That expedited things and it finally went up in the South Terminal for a number of years, which was a different location from where it was originally intended. Ultimately, they deaccessioned it without telling me. So I got contacted by a different person, Michael Brown, who knew Bernice Bing. He recognized my work and contacted me. He used to collect a lot of Asian American contemporary art. So he said, hey, I think I just saw this painting that you did and it was up for auction at Butterfield. That was a stupid place to try to get rid of it, right?

So I contacted the Arts Commission and with my dad's help I essentially bought my painting back for $500. I said, “you know, you're probably not unloading this at this point so I can take it off your hands. You won't have to pay storage fees or whatever.” So now it's with my best friend from college in her living room.

B&A: Their loss! Amazing how you got the painting back.

Thank you so much for sharing your time and your memories. And for your paintings and photographs!

LC: One of my early paintings has recently been acquired by the Smithsonian .

JJ: All the best. Bye.