ARTIST INTERVIEWS SFAC Equity Interviews

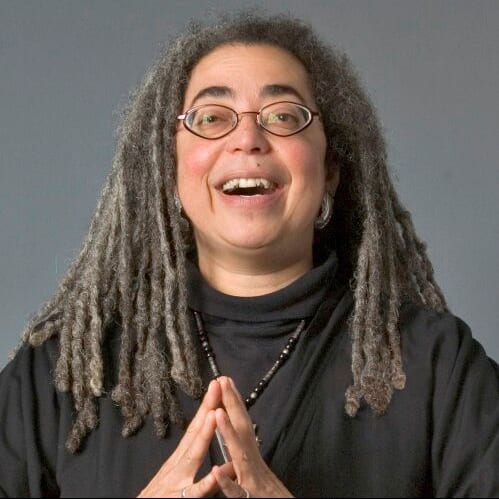

Rhodessa Jones

In 1989, on the basis of material developed while conducting classes at the San Francisco County Jail, Rhodessa Jones created “Big Butt Girls, Hard Headed Women,” a performance piece based on the lives of the incarcerated women she encountered.

During the work's creation, Jones and jail officials were made aware of issues that were specific to female inmates, such as guilt, depression, and self-loathing, which arose in response to feelings of failure in the face of community. These issues directly contribute to recidivism among female offenders. Based on this observation, Jones founded THE MEDEA PROJECT: THEATER FOR INCARCERATED WOMEN to explore whether an arts-based approach could help reduce the numbers of women returning to jail.

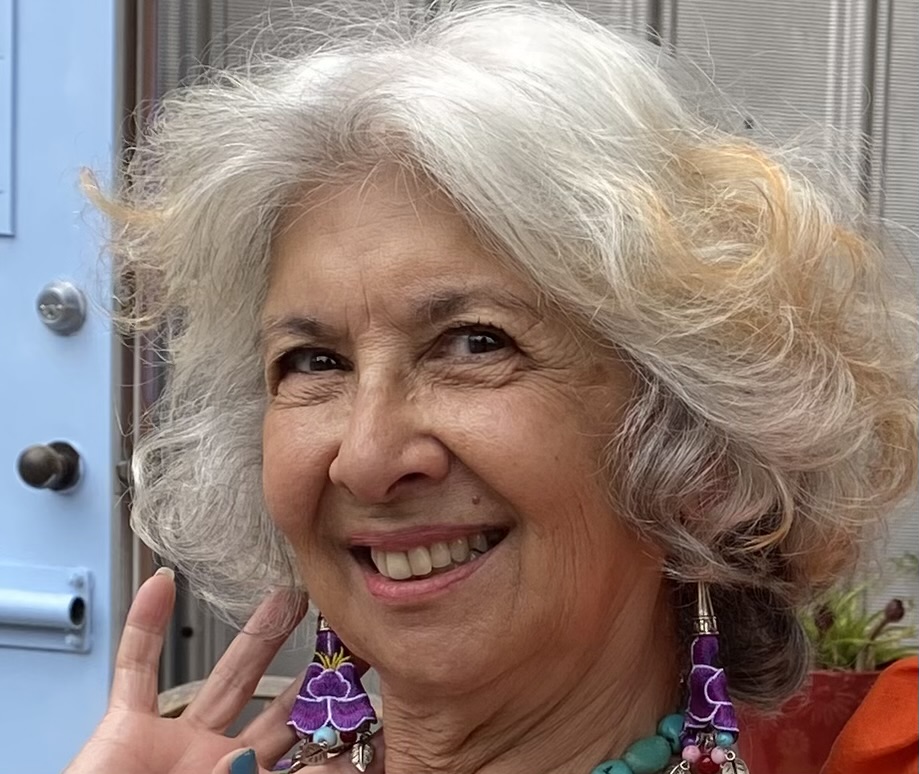

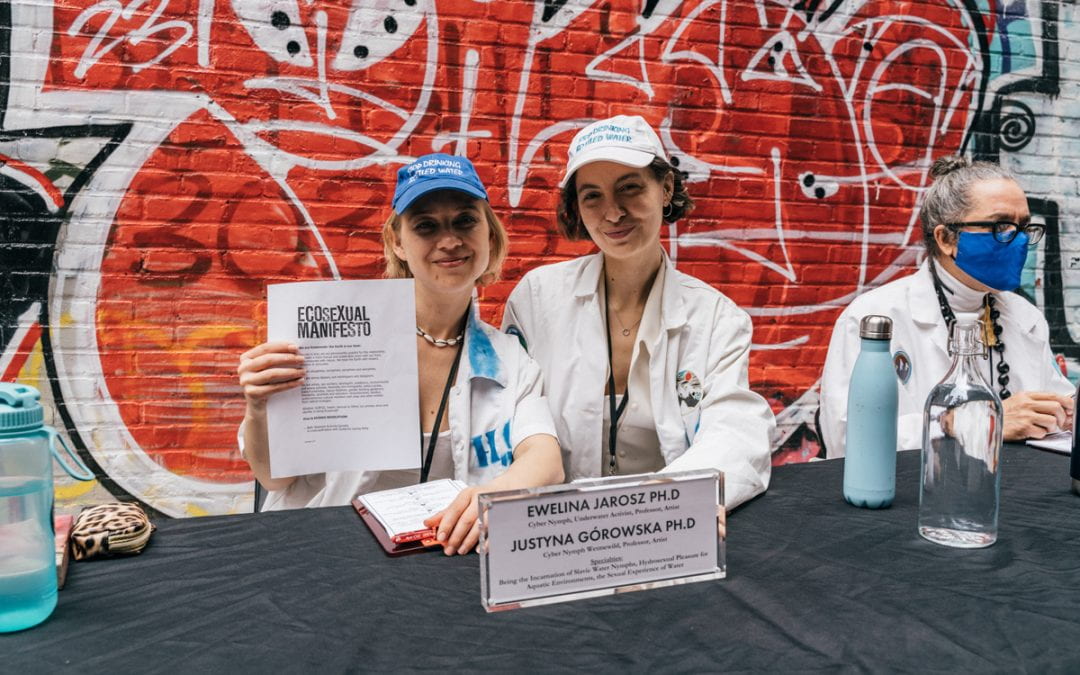

Beth Stephens & Annie Sprinkle: Hi Rhodessa. Beth Stephens and I have a nonprofit called EARTH Lab SF. We do environmental art through an ecosexual and environmental justice lens. We got a grant from the San Francisco Arts Commission to interview 10 important artists like you.

So in a nutshell, we're recording the history of GLBTQ and BIPOC artists and activists who changed things in a big way in the 70s, 80s, and 90s. On June 1st, 2024 we'll present our findings at the Main Branch of the San Francisco Public Library and launch this archive online. Beth has been a professor at UC Santa Cruz for 30+years.

RJ: Is that where Angela Davis is?

B&A: Yes! She's retired, but she was at an event the other night.

RJ: Hi Jeff. How are you?

Jeff Jones: Hi Rhodessa, I'm doing well.

Let's start. We can begin the interview with some background on where you grew up and how you got to San Francisco.

RJ: I was born in Florida. My mother and father were migrant farmworkers and they got their first agricultural contract the year that I was born, in 1948. My dad gathered some people together, got a couple of vehicles, and we drove from our home in Florida all the way up to New Jersey, picking fruits and vegetables. We were gone for 5, 6, even 7 months a year. After a point, my mother decided we had to stop because she wanted us to have a better education than she and my dad had received. So we ended up living in upstate New York outside of Rochester, NY. We settled in a little town called Wayland; I graduated from high school there.

I fell in love with Riley, a crazy Irishman. We met in Rochester and ended up going to Costa Rica because we wanted to leave the United States. We had some friends in Bogotá, but when we got to the border in Colombia, they wouldn't let us into the country because we were hippies and we didn't have any money. I had my kid with me, she was 9. My kid was born when I was 16 years old and I was still in high school.

We had been living in Costa Rica and my daughter got really ill. I had friends in Palo Alto, California and they sent me the money so I could come to California to take care of her. She had gotten some bad bug. She was really sick with a high fever. I always tell people it was jungle fever. We had to travel from Costa Rica back to LA and then up to Palo Alto. We moved to San Francisco in 1973 or 74.

B&A: We were reading about how you supported yourself while you raised your kid. Would it be possible for you to talk a little bit about that?

RJ: Sure. I was dancing with a company called Tumbleweed, which was a women's dance company here in San Francisco. All of the dancers who were performing and making art were also dancing nude at night. When I got word of it, I thought I could do that. I'd been an artist's model and nudity was nothing to me. They wouldn't hire me in North Beach, because they didn’t hire black girls then in North Beach. So I ended up going to the Tenderloin. There I met a great couple, who had set up Fantasies in the Flesh. They thought I was so cute, and I had my wig and great legs and they said, “Sugar, you can work here with us.” They didn't want me to wear my Donna Summer wig. They were saying, “Oh, you are so much more beautiful, so much more dignified, without your Donna Summer wig.” And I said, “Girls, this ain’t about no dignity down here.”

We had a great time. The place was owned by a guy named Al Brown, who kind of fed on young black women. I liked to read. One night I was reading Shogun and I put the book down to go on stage. James Clavel the author of Shogun just happened to be at the club. When I come off, Al says, “Which one of you bitches is reading Shogun?” I said, “I'm reading it.” He said, “Well, this is the author.” Mr Clavel offered me his autograph but I said, “No thanks darling. I have your book. I don't need your autograph.”

It was an interesting time. I started to flex my femininity and my feminine politics. The management didn't feel responsible to clean up the club, instructing the dancers to do it. They felt like we were naked, dancing, and that we should clean up. One night, a woman was lying on stage, turning around and a mouse ran across her body. She freaked out. We all freaked out.

Al said, “Well, clean the place up.” I said, “Oh, no, no, no; secretaries do not clean up offices, Sir.” He had decided I was a cop. I said honey, “I'm many things, but I'm not a cop.” And, he said, “I got my eye on you, Lily.” And the women were curious as to who I was because I had an opinion and that was out of character.

This was an incredible time in San Francisco. But after the assassinations at City Hall, I remember being afraid. The peep-show booths at Fantasies in the Flesh had two sections. I sat behind a window and customers on the other side would put in coins and the curtain would open. I would just sit there with my legs open, you know, because I figured that's what they wanted to see. Later, I wrote a performance piece entitled, The Legend of Lily Overstreet; it was about nude dancing in America.

The big questions for me were what do men want from women and what do women want from men? And why do sex and race make such interesting bedfellows? These are the questions that I posted in my journal as I started to write Legend of Lily Overstreet. There was a young black guy whose job was to clean the cum off of the windows. At first he thought he was gonna get to peek at naked women. I said, “No, no, honey, this is a job.” And he and I started talking and it turns out he went to San Francisco State. He brought in books by Franz Fanon, books about race and culture. He and I started talking about life and dreams. I saw him opening his eyes to the fact that this was just “a job”.

I wasn’t a bimbo; I wasn’t sex crazed- I was working. I remember once while I was working, I would play Mose Alison’s music. A guy came in and said, “Who's playing this music?” And I said, “I am. You're Mose Alison!” And he asked incredulously, “you can see me??” And then he just left. Once Richard Pryor came in and in Richard Pryor fashion, he tucked money into all the windows treating all the customers. He left quickly as well.

I told my family what I was doing. I said, “I'm dancing nude downtown”. My father ordered my brother to “go see what's happening with Rho. See if she's okay.” So one night I looked up and my little brother was looking at me in the window like, “Oh my god.” And he leaves quickly because I'm his big sister. But he reported to my dad that I was safe. I was just dancing, I felt loved and cared for. I wasn't judged.

I was judged by the black women in the San Francisco community. They thought I could do it, but I shouldn’t talk about it. Every woman was so politically invested, that they were disappointed in me. I said, “Honey, I got it so I will flaunt it.” I had a lot of fun. I was outrageous and ahead of my time.

B&A: What years were those, when you worked in the Tenderloin.

RJ: Mayor Moscone was assassinated in 1978. One of the fears that I had was that somebody would go on a shooting spree and they would come in and shoot all the nude girls sitting behind the glass. That's how freaky it was.

We were told, inevitably, we were gonna get busted. So every night I had my fur coat. Sure enough, the raid happened and the police didn't really let us put on clothes, but I had my fur coat.

At Fantasies in the Flesh, we would take turns managing. On this particular night, a young blonde girl confessed to me that she was only 15. I said, “oh shit!” The police were kicking down the door and she and I both were trying to run. You couldn't escape into the alley, so we were arrested and taken to the police station and had to stay there all night until Al came and bailed us out.

I met some amazing people. I think a lot about the hookers, the women who were “in the life”, and the kind of men they attracted. I remember there was an old black man who was probably in his late seventies and his wife had died. He was lonely so he would come down and see me. I'd have my feet up on the glass and he would put his hands on the glass where my feet were and act as if he was rubbing my feet and tell me all about his wife. He would come in often and look at me and talk to me.

Then there was a young sailor from Iowa, a young white corn-fed boy, with big blue eyes and pink cheeks. He had never ever seen a naked black woman before. He and his friends all came in together and they’re all looking at me. I said, “No, y'all gotta keep putting the money in the slot.” So this kid comes back later, alone and he says, “You sure are pretty. You’re just about the prettiest woman I've ever seen.” I said, “Thank you, but you gotta put more money in the slot.”

B&A: Do you think any of the skills you learned working at that club in the Tenderloin helped you in your art career? How did your life as a sex worker translate to your role as a creator of theater?

RJ: Well, other than shaking my nude body, I wasn't interested in being a sex worker. I loved the very interesting exchange of energies. I paid attention to all that stuff. I just took it into the realm of art making. Cause it's all art. It's artwork.

B&A: Performance art for sure. How long did you do sex work? How do you feel now about having done that work?

RJ: I started dancing nude at 30, and I worked in that business for probably 5, 6, 7 years. I'm proud of myself. I benefited from having been a nude dancer and I think I freed some younger people. They think they wanna get down and dirty and I'm like, “honey, if you have great sex with somebody, that's wonderful, but it's not your full life. Don't get caught up in throwing it all in one pile.” I think I've learned how to be honest and clear about so many things because of the journey I've taken.

Beth: There are so many artists who’ve done sex work here in San Francisco. Michelle Tea, Carol Queen, Madison Young, who is our chosen daughter. There are so many people who became artists because they learned something about sex, or performance or care.

JJ: Back to Rhodessa. When I arrived here, you were performing in a church over on Market Street.

RJ: It was the Eureka Theater. I had evolved and wanted to put a show on stage.

B&A: Your show was The Legend of Lily Overstreet. Was that your stage name?

RJ: Yes, that was my dancer name, “Lily Overstreet” from New Orleans.

JJ: So, my question is, why did you stage this work in the gay community?

RJ: Well they found me. Some nights my audiences were all just gay boys from the Castro who'd be sitting there. The gay guys were great to me. There was a bookstore in the Castro called “Does your Mother Know You're Here?” That was a song that I had created for the show. I don't know what the chemistry was but the place would be full of gay men and it would sell out. That’s one way dancing helped my career— I learned this queer language. “Oh stop. Quit. You better work!” I mean, I heard this stuff through the men who were out in the audience. They were so encouraging.

B&A: Was it a solo performance?

RJ: Yes. I wanted to be seen. I wanted to be heard. I wrote everything myself. The most popular black actress at the time was Cicely Tyson, who had done Miss Jane Pittman. I wanted my show to be out front. I already had some notoriety in the dance world because I was so strong, outrageous and courageous.

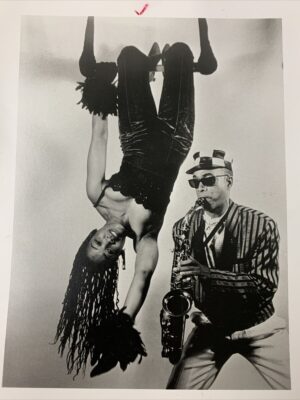

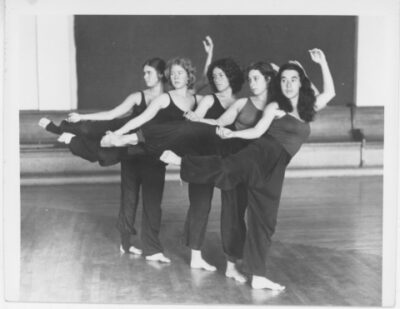

Simultaneously, I was also performing with Tumbleweed, the dance company. We carried each other using contact improvisation. We danced naked. We did rope work, flipping and hanging upside down. Tumbleweed had some notoriety and the country was just opening up.

B&A: The one-woman show was a particularly new American art form. Dramatic soloists.

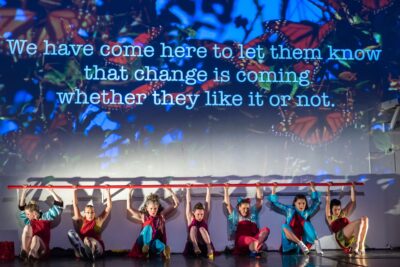

RJ: Yes. Now in my work with incarcerated women, I tell them, “tell the truth and shame the devil. Practice Revolution.”

I was trying to find my way and doing my show gave me a place. My brother Bill T. Jones, the choreographer, used to joke that we were incredible exhibitionists. We knew that we were more attractive than most people and we wanted the art world to make room for us to do our art.

B&A: When did you get involved with Idris Ackamoor and Cultural Odyssey?

B&A: When did you get involved with Idris Ackamoor and Cultural Odyssey?

RJ: The late 1970s, early 1980s, I met Idris Ackamoor. We immediately had a connection. He liked my spunk and my drive. People had this idea that I was a man-eater. I really wasn't. I was just independent and Idris recognized this. We talked for almost a year before we got serious and sexually involved. We had already toured Europe and one day he told me to quit my day job to be artists full time.

JJ: Okay, so we're now up to 1981, 82 or so. Cultural Odyssey was the first black arts group that became a nonprofit that I'm aware of except for Wajumbe. So you two were the only nonprofits in the black community involved with Grants for the Arts except for the African American Historical Society.

RJ: The thing I really admired about Idris Ackamoor was that he just had no problem stepping up to the person we were working with and asking for the money. He'd say, “okay man, when do we get paid?” I still think he's one of the most amazing business artists that I know. He wasn't afraid of asking for what was his. He was very honorable and he would make deals. But you better come through.

I remember being in Berlin with Cecil Brown, the writer. I was doing some nude work in Berlin and this crazy woman came to the club. She was taking us over to her house for dinner, but then she pulled out a gun. Cecil said, “Whoa, what the hell?” And she said, “Do YOU have a gun?” I think the goddamn gun went off.

I remember being in Berlin with Cecil Brown, the writer. I was doing some nude work in Berlin and this crazy woman came to the club. She was taking us over to her house for dinner, but then she pulled out a gun. Cecil said, “Whoa, what the hell?” And she said, “Do YOU have a gun?” I think the goddamn gun went off.

I'm so glad that Cecil and Idris stayed with me because she wanted me to go with her, but I don't know what that would have been like. You know, Idris is not a huge guy, but don't mess with him. He will run through you with his anger and his indignation; I’ve seen him turn into a stiletto. He's not a gangster but he can go there.

Idris and I weren’t even aware of it at first, that I was now a part of Cultural Odyssey. We were writing grants. We were going to meetings. We were going to things set up by the NEA because it was the way to the funding. You had to know how to raise money and we knew that we had the stories. We took the Legend of Lily Overstreet and created a whole score. From there, Keith Haring did the sets for it, because he was a friend of my brother Bill. We just liked to be seen. We wanted to be honored for what we did.

JJ: I remember Cultural Odyssey as the only contemporary arts group in the black community that wasn’t afraid to really be who you were, back there in the mid-1980s. You were not a historical society; you were contemporary artists. At that time the only person in the Latino community like that was René Yañez.

RJ: Yes, exactly.

JJ: So, in 1985, when I did my first report about City arts funding, I found that the black community got less than 1% of city funding, Latinos got less than 1%, and the queers got less than 1% and the Asians got almost 2%. Collectively, we got 5%. That was where things were in 1985.

RJ: Well, we're still up against the Ballet and the Opera right?. They are still getting most of the money.

JJ: If I remember correctly, you started the Medea Project around this time. Could you talk a bit about the Medea Project?

RJ: Well, The California Arts Council awarded the Sheriff’s Department a grant to hire me as a resident artist in the Women’s jail. My job was to go into the jails and teach aerobics to incarcerated women. Looking back, I realize that they just didn't know what else to do with all of these women in jail.

RJ: Well, The California Arts Council awarded the Sheriff’s Department a grant to hire me as a resident artist in the Women’s jail. My job was to go into the jails and teach aerobics to incarcerated women. Looking back, I realize that they just didn't know what else to do with all of these women in jail.

So they thought, “Well, Rhodessa Jones looks like them and she can teach them aerobics.” They were largely black women incarcerated because of crack cocaine. I started going to the Hall of Justice on Bryant Street. The women were not interested in exercising. They would look at me like, “Bitch, please.” And I would respond by doing cartwheels and handstands.

I was turning 42 or 43 years old and I started talking about my daughter who just got married. I talked about being a grandma, and these women were like, “Who the hell is this?” And then one woman asked, “Can we just talk?” And I said, “Yes. As long as we agree that everybody's story is valid. Everybody has a right to her story. And everything we say stays here.”

Then we began trading stories of how these women arrived in jail and became who they were. After a while, it wasn't just black women. It became more multicultural and diverse, a snapshot of San Francisco. The women were eager to share the circle. Michael Hennessey, the sheriff of San Francisco county became aware of what was happening with the work that I did in the jail.

My first time being in the jails, there was a young black woman who decided she was gonna challenge me. She said, “Wanna play basketball?” While I was attempting to create a space where we as a group of women would do some movement and some talking and some dancing, she wouldn't put the basketball down. She was dribbling. I thought, “this is my right of passage. If I don't make this happen, I am nothing in this place.”

The other women were like, “Why don’t you stop, Deborah?” And she's dribbling and catching the ball and finally I had these two little angels on my shoulders, a little black angel and a white angel. And the little black angel said, “You go and snatch that ball from that bitch.” And I did it! I went out and I grabbed the ball.

I said, “let me tell you something. I'm going home at noon. They pay me to be here. You're in lockdown. Who's smarter?” And she started whining about jive ass black girls from fancy schools and I said, “Call it what you want honey, they're paying me and the deputies are watching to see if I’m ok and if I can handle it.” Then I said, “Deborah, are we okay?” All of a sudden she's like, “Ummmm, we're okay.” Today, she’s still doing okay. All this got back to Sheriff Hennessey. And then I met Sean Reynolds, who became my mentor.

JJ: At this time, I was Mike Hennessey’s grant writer. I had heard about Shawn Reynolds, technically a social worker, and about you, I recall her saying to me “These women need more than aerobics!”

RJ: I had two brothers who were cops. My brother Steve in San Francisco and my brother Gus in the East Bay. They turned me on to the welfare fund that cops have for when they need a break, or when they're gonna party. I told Hennessey that I wanted to put the women prisoners on public stages.

He said, “Well, tell me how we're gonna do it.” He was kind of amused. I told him the City has these funds where we can pay the cops overtime to take the women out under guard. He was just fascinated. I had done my homework. My plan was to take the women from the jail to the theaters under guard.

I taught drama, I taught writing, I taught everything inside. I wanted the chains to be removed from them. But I made the cast—both the prisoners and the professional actresses-- enter the stage accompanied by uniformed sheriff deputies. Sheriff Hennessey showed up to every opening night with his father, sometimes with his wife. Then I knew to invite this guy up on stage. He was the man. He just loved that.

JJ: I worked in his campaign the first year I came here. So when he became sheriff, I stayed in touch with him and I also knew several of the people in the Sheriff's Department from politics. One was Connie O’ Connor and another was Louise Minick. All three of us were on the Executive Committee of the Alice B.Toklas Democratic Club. Also at this point, my grant writing partner was Ellen Gavin. I think Ellen was producing the Medea project.

RJ: Yes.

JJ: It all fit together because it was a very small community. We all knew each other then. It's bigger now. Things don’t happen the same way because there are too many people.

Beth: Oh, it's still a pretty small world, Jeff. Not as small as it used to be, but it is. The problem is there’s some infighting in the art world and the pool of money is not growing.

RJ: Ellen’s in LA now, right? She’s on the California Arts Council.

JJ: Yes, the CAC. Recently, we seem to be talking frequently. Moving on… So the Medea Project basically pre-figured reality TV. The white people in the audience were listening to Black women telling stories that were totally foreign and unimaginable to white people.

RJ: Yes, and in the beginning, I had some pretty heavy hitters. They helped me to ground the words and get women to stand up straight and tell the truth. We had a lot of fun. Shawn Reynolds came in and she told the women she was a lesbian. And the women said, “Can we say that?” and Shawn said “If you're a lesbian, then yes.”

You could see women flowering. Wow, it was a new day. They didn’t have to hide, and I was just so grateful. Amy Meuller, a friend of Ellen’s who used to be with the Playwrights Festival worked with me for a while too. We had a great time. We grew and we were able to feed each other all of these ideas through experimental theater.

I think that's what gave women, and men, the room to speak their own truths. And that's San Francisco. It was Martha Graham who said, “People from California believe anything is possible” That was a thought that I carried around inside of me for a long time; I'm from California and I can make this happen.

JJ: The first Medea Project production was Reality is just Outside the Window. Your solo show Big Butt Girls, Hard-headed Women was also about incarcerated women. You were doing something very different than everyone else in the theater world. Medea wasn’t just a solo performance. It was a reality-based performance featuring both professional actors and prisoners. The weird thing was that the audience couldn't always tell who was a prisoner and who was a professional actor.

JJ: The first Medea Project production was Reality is just Outside the Window. Your solo show Big Butt Girls, Hard-headed Women was also about incarcerated women. You were doing something very different than everyone else in the theater world. Medea wasn’t just a solo performance. It was a reality-based performance featuring both professional actors and prisoners. The weird thing was that the audience couldn't always tell who was a prisoner and who was a professional actor.

RJ: That was a running joke for us, trying to figure out who's the convict and who's not. All I would say to the women is that when we move on stage, we’ve got to move like an army. If people that knew some of the women from the streets got word about the show, they would come and they wanted to try to rap. That's why I always sat in the theater. I never let them just run their mouths.

Jack Carpenter, the Technical Producer everyone used at that time, said to me, “Rhodessa, you have to stay with this process because when you're upfront, they are so focused.” I'm glad that I was able to manipulate the whole thing and give the women a focus.

It was like giving them eyeballs saying, “Come on, stay with me and we can talk about anything.” I remember one piece that a girl wrote. It was all about, “Hey baby. How much to fuck?” She had been a prostitute on the streets and she wrote this great little jingle about fucking and sucking and how much it cost. She asked me, “Can we say it?” I said, “We're gonna say the whole thing.” I guess it was experimental. But it was time for more people in our community to speak their truths.

JJ: Then if we move forward to 1989, I was writing all these grants for your piece entitled, I Think It's Gonna Work Out Fine.

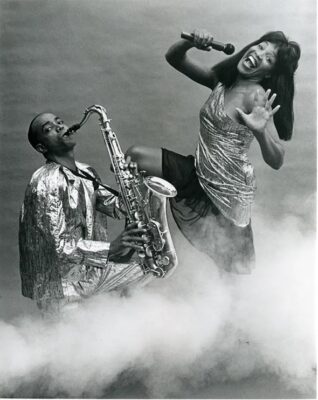

RJ: Oh yeah, the Ike and Tina Turner show. That was a duet with a musical score. Again, it was so original in how we did it.

JJ: Right before the show opened there was the Loma Prieta earthquake. You were staging this production at the Valencia Rose right? It really became the gay performance space. I wrote the first grants for that building also in 1983 I think. It was Tom Ammiano’s brainchild, along with Hank Wilson and Ron Lanza.

But back to the show. It sold out almost all the time. How were you thinking about that work? Did you see yourself as Tina Turner?

RJ: We just thought it would be a great piece to put on. Ed Bullins wrote it and Brian Freeman directed us. I remember Tina Turner was writing her book and all of a sudden Tina left Ike and it was big news. It was a perfect piece for Idris and me. Idris was a little nervous because people got him confused with Ike and were sometimes rude to him because he played the Ike character so well. But it was a lot of fun because it was fresh and bold. And it was fun working with Brian and Ed and having a band. It was timely. I had great legs, so I could do it.

That's one of those pieces I am so proud of having been able to pull off. We did it everywhere,—in Chicago, New York at La Mama, around Europe. We had to remind Europeans that Tina Turner was a real person, cause everybody just wanted me to sing and strut my stuff on the stage. Nobody was interested in Tina’s personal story in Europe. They were interested in her only as a performer.

JJ: Did Pam Peniston have anything to do with Medea?

RJ: Not on the first Medea. We started working together on Perfect Courage, a production that was the opening night show for Festival 2000. Pam and I are still working together on the Medea piece that we're doing in the Bayview.

B&A: When is that piece going to be up, Rhodessa?

B&A: When is that piece going to be up, Rhodessa?

RJ: We're gonna do a workshop performance on June 14th. Then we're gonna move to Brava and continue to build on it.

JJ: Great. So let’s return to Festival 2000.

RJ: Yeah, Perfect Courage opened the Festival. We didn't know all the behind-the-scenes stuff that was going on about lack of money. But I think we got paid. There were people that didn't get paid. It was a great idea but it fell through the cracks.

Whatever happened to Lenny Sloan? They brought him in as the Director of Festival 2000, right? I think he moved to New Orleans. I was so proud to be a part of the planning committee for Festival 2000. But then to find out that behind the scenes, there was no money? That was drama. But I still had a lot of fun.

I just had dinner with Brian Freeman 2 or 3 weeks ago: he did Perfect Courage with us. I often tell him that Coleman Domingo is getting all this coverage for Bayard Ruskin but Brian Freeman is the person that introduced the community to who Ruskin was.

JJ: So, going back into the history, it was Festival 2000 that got us the cultural equity grants program. That's where it came from.

RJ: You know more about the backstory than me because you and Idris talked a lot about that. But I'm glad we did it. Cultural Equity is not a bad thing. We deserve it, damn it.

JJ: Yeah, when I look back on Festival 2000, I thought it was great that Grants For the Arts had thousands of dollars that they could spend on anything. They spent $35,000 to put a car in that little outside space between the Opera House and the veterans building because some car company was sponsoring some opera production. I think Grants For the Arts spent $35,000 on that. But when it came time to bail out the people who got screwed at Festival 2000, suddenly there was no money. Money for the opera or ballet, but not for anyone else. Even though it took us two years, Festival 2000 launched the Task Force that resulted in the Cultural Equity Grants program.

RJ: Wow, Jeff, I have to give you your props. You were wheeling and dealing, baby, and a lot of people didn't like seeing you coming because you were gonna let them have it. That was one of the things the artists talked about; That you were a bit more than just a grant writer. You had your flag and your bully club and all that other stuff too. I applaud you for that. I really do. I love the history of how you did it. You're making me remember things that I'd for sure forgotten.

JJ: And you’re still out there. Lily Overstreet showed again 20 years after the first one.

B&A: Oh, yeah. At Fort Mason, right?

RJ: Yes, and it was outrageous. Yeah, Lily had turned 50. It was Lily's 50th birthday party.

B&A: When's Lily turning 75? You could have another party.

RJ: Well, I'm 75 now, so let me give it some thought.

JJ:. I'm gonna be 80 soon and, I hope, I’m every bit as obnoxious as I used to be.

RJ: Yeah, you really are the classic old pain in the ass and that's what we need.

B&A: So, after that, you continued doing the Medea Project, right?

RJ: Yeah, well, all these women would not let it die. I got invited all over the world; Egypt, South Africa, the Caribbean. We were down south. We were in New York. We were everywhere. When I was in South Africa, I actually built a whole company of African women in jail. The Medea Project was very malleable, and just right on time as a piece of artwork.

B&A: So how did you become a resident artist at Yale and Dartmouth and all these other places?

RJ: Well, I was one of the early people doing art as social change. Also, I was from California, where there was this idea that you could really create artwork rooted in politics. I think that's what it was. I had a great time at Yale. They didn't know what to do with me because I didn't have a ton of letters after my name. But the students loved me. I got them to write. How do I do what I do?

I have a chair right now at Cornell. I'm able to bring members of the Medea Project to teach; Angela Wilson and Felicia Scads, the ex-offenders. They teach the project now and I just sit and witness it. But to answer your question, I think that I helped give birth to the idea of artists creating social change. So when I go to colleges and universities there are all these students who are interested in talking about that and being a part of it.

B&A: So you’ve had a good experience working with universities?

RJ: I've worked at Yale and Cornell. I was fascinated that they wanted me to come and talk about my work and my life. People are telling me now, “You ought to go back to the university.” I go back when they invite me and they pay me well. I’ll do a residency and spend a week working with the students. For my next residency at New York’s Hamilton College, the students will develop a performance piece about gun violence.

B&A: Now at New York University there is a program where you can get a Masters in Theater & Social Change. That's clearly something that came from your work.

RJ: Yes. Was it at the University of Michigan or Pittsburgh that had prisons attached to the campuses? Cornell has a prison project. You can go into the prisons while you're there and that's been a pretty amazing thing to be a part of too. But it's still largely men, not women.

Beth: Rhodessa, we’ve gotta get you down to UC Santa Cruz where there is an Institute for Arts and Sciences. It’s all prison abolitionist programming. Plus I started a program in the Art Department called the Environmental Art and Social Practice Program.

RJ: Oh, that'd be great. Maybe I can bring my crew and we can work with the students to make a performance. I’d really like to make that happen.

B&A: That'd be beautiful. I’m curious to know, back in the day, what theaters and what kinds of spaces did you feel most comfortable working in? What artists were you going to see?

RJ: Well, you know, in my early youth, my sisters and I were girly girls, very influenced by Motown. We used to sneak in and perform at this bowling alley in Rochester NY because we weren’t old enough to be in a bar. My mother had been a singer in a gospel group, so singing and dancing were the early things in my life. Every holiday, Christmas, Easter, Thanksgiving, you were expected to put on a show. That's how I cut my teeth.

Then, of course, after I moved to San Francisco, I was raising my kid in Potrero Hill and took performing for granted. Then Teresa Dickinson, the founder of Tumbleweed, asked me if I could come and dance with the company. All of a sudden I was back into modern dance and contact improvisation with these women. So that's where I met Mangrove and John La Fan and Robert Henry Johnson.

Yes, these were the people that I was interacting with all the time, and my brother Bill, and his partner Arnie Zane. I was going to New York and seeing them and going to La Mama. That was just some crazy stuff going down. But I liked it.

B&A: You told the funniest damn story about Bonnie Ora Sherk when you went to New York in your bus.

RJ: Oh, Bonnie. What a trip the Farm was, huh? The Farm was part of shaping my consciousness because it was a performance space and a farm located at Potrero and 26th street in the Mission.

So back to your question about what shaped me. There were all these ideas coming down about what theater could be and what you could manifest through stage work. And I had a children's company. We did political theater. I worked with the Mime Troupe too for a while. I did love that.

B&A: Did you ever perform at Glide Church in the Tenderloin?

RJ: The Medea Project and I have performed at Glide Church; we created a piece based on bits and pieces of classical literature. I used to love Janice Mirikitani. Janice was really kind to me and a great poet. She would ask me to come to her poetry reading and I'd go. I got my PhD at the edge of the world. I was looking at everything.

B&A: What venues did you go to here in San Francisco in the 70s and 80s. What was your home theater?

RJ: I remember performing at The Art Institute in San Francisco, we were invited there often. The Eureka Theater was another venue that I worked at a lot. Like I said, I was a hippie chick before I was a performance artist. So I loved working at outdoor venues. When I was working with my brother Bill T Jones and Arnie Zane, I remember Peter Coyote asked us, “What's the Jones company? A band of junkies?” And we said, “Oh no, we're family.” I learned early that the stage was this incredible space to share energy from, or to protest. But theater kind of found me. I didn’t go around looking for it.

JJ: The Eureka Theater where you performed Lily Overstreet had as its Artistic Director --Tony Taccone; Later, he commissioned Tony Kushner to write Angels in America and the Eureka premiered it in San Francisco.

RJ: I auditioned for late night with Julie Hebert. She really liked me. Julie was really the key to me being there at all.

B&A: You also performed at Brava Theatre. Now you're at the Bayview Opera House.

RJ: Yes I am at the Bayview Opera House right now, it's great to be back and funded by Black on Both Sides for Life on the Swerve. But Brava has been the Medea Project’s home in San Francisco for a long time.

JJ: In addition to your long history of creating new, innovative and experimental work, Cultural Odyssey worked so well that you both have a retirement package, and that’s rare for a small-to-midsize non-profit arts company.

RJ: Yeah, we do. I've already bought a house in Houston, Texas. It’s a 5-bedroom house with a swimming pool. It was only $400,000. My granddaughter, my daughter, and my great grandson are living there now. I like that area. But nothing compares to the Bay Area in a lot of ways.

B&A: What do you see yourself doing in the future? Do you think you're ever going to retire?

RJ: Well, I always say that I am, but I am actually working on a book. The book is titled, Nudging the Memories. It’s a handbook about how I make theater with “other” populations and I'm only halfway through but it's becoming a collection of my own stories as well as the stories of the women that I work with. My sister and I are also working on something entitled Just Outside of Babylon. It's about living in America, coming out of a migrant family. So I have those two projects happening.

I might go back and make my own documentary of the Medea Project, just to see the people in the group that have grown immensely like Angela Wilson. She runs the women's unit with the sheriff’s department and I met her in jail. She was a addict and now she runs this program and she's getting her degree at SF State.

B&A: How many brothers and sisters did you have?

RJ: 12 brothers and sisters.

B&A: Wow. So, our last question is, as you reflect on your contributions and challenges, what advice or insights would you offer to emerging BIPOC and/or LGBTQ artists who are beginning to navigate their artistic journeys?

RJ: To the people dreaming or being hesitant, I would say, “take some deep breaths, and follow your own heart.” Because that's a hard one. People say, “oh my God, be careful.” But this is all we got. I have grown into my heart, and I trust her. I trust her more than anyone. Yeah, you're gonna get knocked down a few times. That's gonna happen. But trust your own instincts. Trust your heart. There are people who need to hear your stories. Practice revolution.

And don't be afraid to write it down. Lily Overstreet really grew out of the fact that I took a little journal to work with me when I worked at the Tenderloin peep-shows. I'd never done that before. So much was going on. Later I'd go back to this journal and I'd have a lot of things that made sense and a lot that didn’t make any sense at all. But I chronicled my own experience and I think that's a very good tool to be able to hone in and call your own.

Annie: As I'm approaching 70, I'm thinking about the mistakes I made. They always say, “oh, don't be afraid to make mistakes.” But then you’re 70 and you go, “fuck, I made a lot of fucking mistakes.” Do you feel that way?

RJ: Yeah. You look back and you go, “Wow, what was I thinking?” I wish that I had been more careful with my kid who’s a tad wounded by things that I said or did or by the people I exposed her to.

I always tell people I pulled this life out of my ass. There was no school to attend to be an exemplary new dancer. You have to trust in creative survival. Everything that you're handed is a jewel of some sort. Trust it. I am a creative survivalist. I've taken what the world gave me and I've made it work for me.

I think I surprised my daughter, because I have no problem saying, “I hope you can forgive me.” I think she looks at me sometimes and thinks, “You're my mom. What does that mean?” My daughter is so much like my mother. She carries a big stick. My mother would say, “I'm not your friend, I'm your mother.” Okay, but do you have to roar so loud? All in all theater saved my life. If not for theater I’d be a bitch with a very bad attitude, or dead.

B&A: Thank you so much Rhodessa. Thank you for your life’s work, from the peep-show to the theater, to the prison work, to the teaching and to the work you’re doing now.

RJ: Thank you so much. I enjoyed this. It was a walk down memory lane. Thank you, Jeff. It was really interesting. Alrighty. I'll talk to you later. Bye-bye.

JJ: What year did you become the director of the GLBT Historical Society?

JJ: What year did you become the director of the GLBT Historical Society? B&A: According to Wikipedia, Tranny Fest became the San Francisco Transgender Film Festival, and it was the world’s first trans Film Festival. And we were there! Memories are full.

B&A: According to Wikipedia, Tranny Fest became the San Francisco Transgender Film Festival, and it was the world’s first trans Film Festival. And we were there! Memories are full. The wave of trans activism that started in the ‘90s in San Francisco, and later fueled a wave of cultural production, came out of that sensibility. It was a way of meeting the moment with regard to the impact of AIDS—trans women of color engaged in survival sex work had the highest infection rates of any demographic—as well as contesting the historic relationship between trans life and an often transphobic cis-gay and cis-lesbian community.

The wave of trans activism that started in the ‘90s in San Francisco, and later fueled a wave of cultural production, came out of that sensibility. It was a way of meeting the moment with regard to the impact of AIDS—trans women of color engaged in survival sex work had the highest infection rates of any demographic—as well as contesting the historic relationship between trans life and an often transphobic cis-gay and cis-lesbian community. I’m thinking, too, of someone like Jayne County, once a drag queen from the South who hustled her way up to New York City doing sex work, became part of Charles Ludlam’s Theater of the Ridiculous, and became a major punk icon with her band Wayne County and the Electric Chairs before she transitioned. They had this amazing song called If You Don't Want to Fuck Me, Baby, Then Baby, Fuck Off. She brought this total, in-your-face punk sensibility to the work that she was doing. She titled her autobiography Man Enough to Be a Woman. She became a fixture at Max's Kansas City, and her style influenced everybody from the Dolls to Bowie to Lou Reed to Blondie. She was an incredibly seminal cultural figure. Is that “trans art” now? I think so. By the time the 1990s rolled around, a late-career Jayne County put out an album called Transgender Rock and Roll. And she paints. She has a really interesting outsider-artist style.

I’m thinking, too, of someone like Jayne County, once a drag queen from the South who hustled her way up to New York City doing sex work, became part of Charles Ludlam’s Theater of the Ridiculous, and became a major punk icon with her band Wayne County and the Electric Chairs before she transitioned. They had this amazing song called If You Don't Want to Fuck Me, Baby, Then Baby, Fuck Off. She brought this total, in-your-face punk sensibility to the work that she was doing. She titled her autobiography Man Enough to Be a Woman. She became a fixture at Max's Kansas City, and her style influenced everybody from the Dolls to Bowie to Lou Reed to Blondie. She was an incredibly seminal cultural figure. Is that “trans art” now? I think so. By the time the 1990s rolled around, a late-career Jayne County put out an album called Transgender Rock and Roll. And she paints. She has a really interesting outsider-artist style.

JJ: So when you started Wallflower, did you perceive what you were doing as performance art?

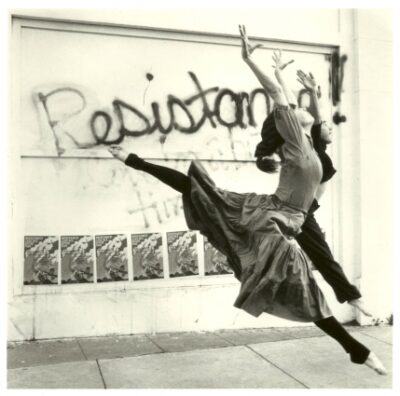

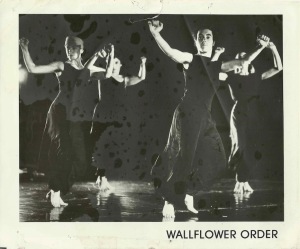

JJ: So when you started Wallflower, did you perceive what you were doing as performance art? KK: When Wallflower moved from Eugene, Oregon to Boston in 1981, we had been touring all over the United States, in Europe and Latin America and our work occupied the intersection where lesbian feminism meets solidarity work, exemplified by Chile’s Pinochet and many other US-propped up dictators across the globe. Lesbians were at the center of most solidarity groups supporting the liberation of Nicaragua and El Salvador. Our work married these two struggles on stage and there was an audience for it wherever we went.

KK: When Wallflower moved from Eugene, Oregon to Boston in 1981, we had been touring all over the United States, in Europe and Latin America and our work occupied the intersection where lesbian feminism meets solidarity work, exemplified by Chile’s Pinochet and many other US-propped up dictators across the globe. Lesbians were at the center of most solidarity groups supporting the liberation of Nicaragua and El Salvador. Our work married these two struggles on stage and there was an audience for it wherever we went.  JJ: I think some of these earlier pieces and events you were producing resonated. What about Furious Feet?

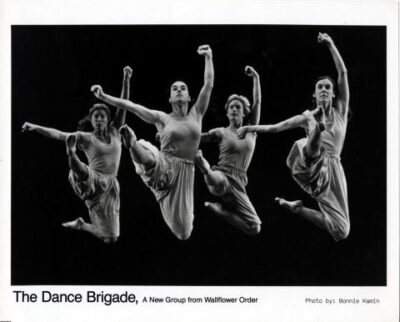

JJ: I think some of these earlier pieces and events you were producing resonated. What about Furious Feet? KK: I feel like in dance everybody works with everybody. All the dancers move through many different choreographers because nobody can afford to pay a company except for the ballet, Michael Smuin, Alonzo King and Sean Dorsey. But most dancers move back and forth.

KK: I feel like in dance everybody works with everybody. All the dancers move through many different choreographers because nobody can afford to pay a company except for the ballet, Michael Smuin, Alonzo King and Sean Dorsey. But most dancers move back and forth. KK: I think definitely The Wallflower Order. Creating that collective was the beginning. I think creating the GRRRl Brigade too. Besides that, I think starting the Lesbian and Gay Dance Festival and the first Festival presenting sky dancers– “Women who Fly through the Air.”

KK: I think definitely The Wallflower Order. Creating that collective was the beginning. I think creating the GRRRl Brigade too. Besides that, I think starting the Lesbian and Gay Dance Festival and the first Festival presenting sky dancers– “Women who Fly through the Air.” KK: You got demonized super bad. I remember when someone came to meet with me—she had just been assigned by the NEA to be Dance Brigade’s Advancement Consultant. They told me “You gotta stop working with Jeff.” I didn't understand what was going on. But I do remember looking at a finished grant that just sat on the floor of the closet because you had written it. It was that you were calling Kary Schulman’s Agency (Grants for the Arts) racist and they were all coming after you.

KK: You got demonized super bad. I remember when someone came to meet with me—she had just been assigned by the NEA to be Dance Brigade’s Advancement Consultant. They told me “You gotta stop working with Jeff.” I didn't understand what was going on. But I do remember looking at a finished grant that just sat on the floor of the closet because you had written it. It was that you were calling Kary Schulman’s Agency (Grants for the Arts) racist and they were all coming after you.